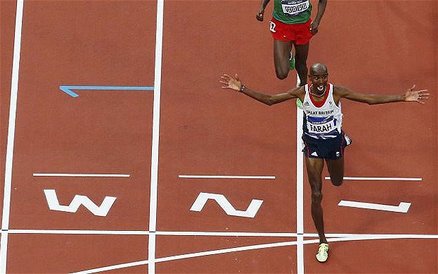

It was two golden evenings last summer which really caught the nation’s imagination. ‘Super Saturday’ and ‘Thriller Thursday’ were nights where the gold medals just kept on coming for Great Britain. It was when the Olympic Stadium came alive and provided defining moments for both the Olympics and Paralympics.

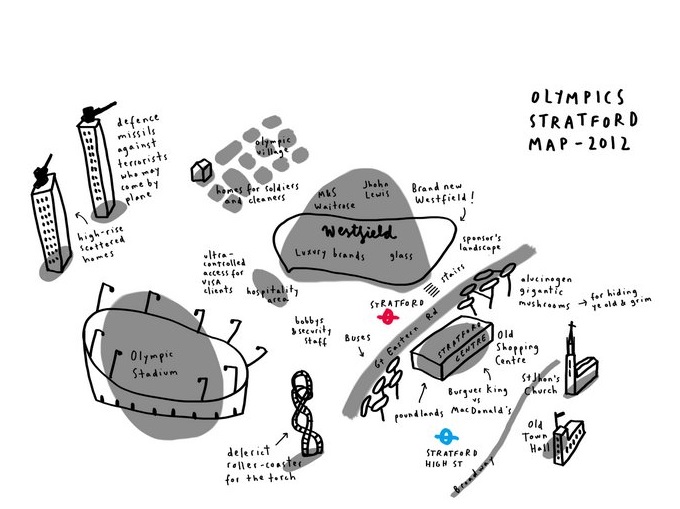

It was the culmination of seven years of hard work which converted a wasteland in East London into a sporting paradise. Land had been flattened and cleared, the contractors sent in and steadily the Olympic Park in Stratford began to take shape. All this was crowned by a glorious Olympic opening ceremony where the world caught a glimpse of a confident Britain in the 21st century. But great sporting moments make great venues, so it was the gold’s around the necks Mo Farah and Hannah Cockcroft et al which really made the Olympic Stadium. After years of anticipation and millions of pounds of public money, those moments provided a focal point to the entire summer.

London 2012 had stopped being something which merely existed on paper and brought real joy to millions of people in the country. And for many that theatre was the Olympic Stadium. It instantly became one of the most recognisable landmarks in London, along with Big Ben, the London Eye and Shakespeare’s Globe theatre. The triangular floodlights fixed the nation’s gaze on the likes of Jess Ennis and Jonnie Peacock. This patch of East London had earned a place in the nation’s heart.

It’s all gone now – the athletes, the spectators and the IOC officials but the stadium still stands. A physical presence for a million memories – a memorial to a wonderful summer. The original plan was to redevelop it after the Games but that has now been shelved as many want to keep the stadium largely as it is in order to protect a wonderful summer. The issue over the future tenants of the stadium is part of this debate, as is how to provide a fitting legacy. A compromise has been sought: a football club to fulfil the commercial side of the equation but the running track will remain for future generations. The hope is that the stadium will be a wonderful theatre for decades to come.

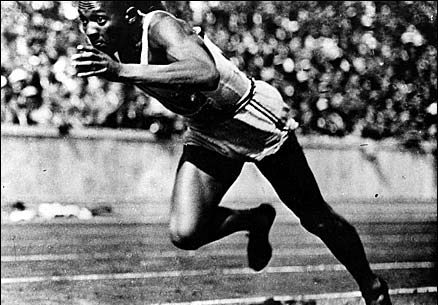

The Olympic Stadium in Berlin stands out for different reasons. Built in preparation for the 1936 Olympics, it signalled the growing power and dominance of the Nazi government. The imposing stadium with Aryan statues around the parameter welcomed the world. It was Hitler’s vision. However, the 1936 Olympics also represented a triumph for humanity. Jesse Owens, the black American sprinter, fundamentally undermined Hitler’s Aryan principles by storming to four gold medals.

After the Cold War, a question mark hung over the stadium. What to do with a stadium which had such explicit links to Hitler and the Nazi party? There were calls for it to be demolished and to start again. But in preparation for the 2006 Football World Cup, the stadium was renovated with a modern roof. It hosted several matches featuring the German national team and was the showpiece for the final. The stadium subsequently held the 2009 World Athletics Championships where Usain Bolt stormed to victory in the 100 metres setting a new world record in the process. Over half a century after Owens’ extraordinary feats, it was a fitting tribute that the Berlin running track was once again graced with a superstar of world athletics.

Going to the stadium is more than just going to see a sporting event. It is a piece of history – the past sometimes conflicting with the present. The renovated Olympic stadium represents a modern, peaceful and confident Germany but the decision not to demolish indicates the past should never be forgotten, however difficult the questions. More so than any other stadium in the world, the Berlin Olympic stadium represents the difficult passing of history and how it should be remembered.

Olympic stadiums are unique, often built for a specific event and part of a national identity. They are all linked to the wider Olympic movement – the biggest sporting movement around the globe recognised on all five continents. They are dotted all over the world from the Estadio Olímpico Universitario in Mexico City to the Stadio Olympico in Rome. Forming part of a line which can be traced all the way back to the very first Games in Paris in 1896 to last year’s Games in London.

After the party has finished, only the stadium is left. In many cases, the stadium is used for different purposes: baseball in Atlanta, rugby in Sydney and football in Athens. Critics often decry the loss of an athletics purpose but the stadiums maintain the Olympic spirit of a sporting legacy. And the stadiums still hold great Olympic memories: Michael Johnson in Atlanta, Cathy Freeman in Sydney and Liu Xiang in Athens.

Like in London, commercial hard-headiness has to be applied to secure lasting futures for these stadiums. The problems with Beijing’s famous Bird’s Nest stadium, which currently lacks a distinct post-Games purpose, reveals how difficult it is to manage a lasting legacy.

Olympic stadiums are thus a special breed of sporting venue. The help a nation unite, creating an once-in-a-lifetime summer jamboree which is remembered for generations. The world is welcomed to the host city allowing for shared experiences, shared cultures and shared histories. But most importantly, they have produced truly great sporting moments which will be remembered in the annals of time. From Jesse Owens to Carl Lewis and now Usain Bolt everyone remembers their achievements and the locations they took place in.

Olympic stadiums are more than just bricks and mortar.