It is an undeniable fact that children are endlessly curious and therefore natural experimenters. I remember my younger brother pulling worms directly out of the mud and sampling them like spaghetti. I never felt particularly inspired to follow him, but as he got a bit older and started to dismantle not only his own toys, but occasionally mine as well, rather than getting angry I would sometimes join him – much to the grief of our parents – and together we would discover the dark underbelly of Barbie and tamagotchis.

My first encounter with the work of the artist Haroon Mirza (b. 1977) re-kindled a few of these memories. Often piecing together found objects, Mirza mediates relationships between audio and visual works to produce a synthesis and create a correspondence between his various cultural and ideological sources.

As a child Mirza used to dismantle his toys to see how they worked: "I used to try and fix things and, perhaps not knowing how to fix them, I'd make them into something else." He is no less inquisitive today, but his parents can no longer scowl at these Dr Gadget escapades. Mirza observes that when he was a kid “[taking stuff apart] wasn't art … It was something else and it's only art now because it's in the context of an art gallery.” Fingers crosses, Barbie is still in the attic.

Contemporary art jokes aside, Mirza’s work deals with something that is conceptually complex which challenges the audience’s preconceptions. He hopes to transform everyday experiences of 'hearing' noise into something closer to a conscious listening. He plays with recognisable patterns to reorient his viewers and help them to engage more actively in the process of autonomous listening.

One of his works, Adhãn (2009), is a brilliant example of this: by translating the opening bars of a Cat Stevens song into an animated installation, he brings audio into the slightly more immediately comprehensible world of sight. In Adhãn we find a flickering desk lamp, a glass cube collecting condensation, an old radio tuning in and out and a video loop of a cello extract. We simultaneously encounter a well-known song riff as well as a series of slightly odd visuals, producing an experience that is both strangely familiar and quite alien. Rather than making abstract work that remains stiffly conceptual, he strongly appeals to the senses.

Mirza came onto the radar of the art world in 2011 when he won the Northern Art Prize for an installation that placed sound from vintage record players next to projected film clips. Since then he has been rather sought after, winning multiple other prizes and showing at the Vienna Biennale as well as London's famous Lisson Gallery, the Tate Modern, and MoMA in New York.

Mirza – a man of many talents - is also a DJ, and has had his audio collages remixed and released on vinyl by the likes of Factory Floor and Django Django. He claims that he is experimenting with the spaces in between ‘music’, ‘noise’ and ‘art’ and questioning these labels. He notes: “All music is organised sound or organised noise, so as long as you're organising acoustic material, it's just the perception and the context that defines it as music or noise or sound or just a nuisance.”

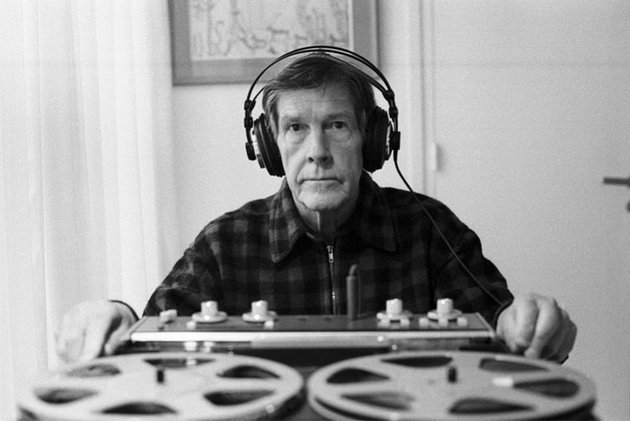

The extremely influential writer, artist and composer John Cage (1912-1992) also questioned the perceptual border between music and non-music. His 1952 composition 4'33 remains unparalleled in its challenge to musicality. You can watch the whole of 4'33 performed live on video here, but don't bother turning up the volume of your speakers: the piece is delivered in the absence of deliberate sound and the musicians who present the work do nothing aside from being present for the duration specified by the title.

Cage's objective here was not simply to have an audience listen to four minutes and thirty-three seconds of silence, but rather to have them engage with their surrounding environment. The piece remains an assault on assumed definitions of musicianship and musical experience. In the same way that Mirza claims that it is simply the gallery context that transforms his creative-destructive experiments into artwork, one could also argue that it is only the visual presence of musicians in 4'33 that gives this piece its place in the world of musical composition.

So if all of this optimistically suggests that the sounds of your weekly rubbish collection or the night time neighbourhood yowling cats are potential chart toppers (or at least slightly off-beat avant-garde tunes), I guess you could make a recording, post it on YouTube and, fingers crossed, it will go viral. However, the challenge that Mirza and Cage posit regarding the merging categories of audio and visual is not arbitrarily left to chance. They might have both destroyed their fair share of household items as children, but the question they pose in the 'adult world' is more to do with the categorised and bureaucratic nature of our lives: the idea that we maintain special compartments for music, for visual art, for noise, for silence, and so on.

The work of Mirza and Cage asks whether these distinctions can be made at all, or whether they are simply rules that we have in place that do no more than prevent us from experiencing things on their own merit or together. I suggest that you listen to 4'33 with total concentration, and decide for yourself...