Minimalist design is primarily recognisable for its less-is-more aesthetic. It has been used as a bastion for architectural innovation and interior design since its explosion in the 1960s as an art movement.

I am always instantly drawn to its attention to clean and bright colour combinations - or often a reduction in colour and attention to black and white lines and shapes - un-fussiness, and emphasis on surface textures. A first encounter with minimalism is like taking a dip in a cool swimming pool after having been on a hot and sticky 10km hike: in one words - refreshing.

Minimalism was influenced by, among other things, Japanese design, which also pays much attention to clarity and simplicity and the frame of mind that a particular space may induce or lend itself to. Within ideals of Japanese Zen the notion of simplicity is not just an aesthetic decision but is in fact invested in the ideals of freedom. Simplicity is believed to reveal the nature of truth and the essence of living. Within Zen, the concept of Wabi-sabi works with the value of simplicity in appreciating the innate quality of an object's materiality.

Minimalist designers and architects strive to strike a balance between plane, shape and lighting, particularly paying attention to the spaces that are left unfurnished or unadorned. We see this particularly in the architectural designs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), who was preoccupied with arranging the various and multiple components of a building in such a way as to produce a physical manifestation of simplicity.

World famous American artist Donald Judd (1929-1994) is known for his attention to spatial clarity and object autonomy. Although Judd began practicing as a painter, he later moved onto sculpture. His work at this point primarily consisted of 'boxes', 'stacks' and 'progressions' – simple object forms made from humble materials such as concrete and plywood, through which he explored the utility of space. He called these pieces 'Specific Objects', arguing that they were neither paintings nor sculptures. For Judd, the relationship between the object, its environment and the viewer were of the utmost importance. He saw the viewer’s presence as integral to the work of art itself, rather than as voyeuristic.

The minimalist movement blurred the boundary between 'household objects' and 'art objects': the undefined liminal space between the two is still a source of anxiety in the art world and among the general public. Judd often produced work that was functional - particularly so with his architectural structures in Texas and his furniture designs - or made pieces that were 'autonomous', meaning that they existed entirely and wholly in themselves.

In quite direct relation to the Japanese ideals of simplicity and equality, Judd was interested in how spaces could be made democratic: how spatial hierarchy could be avoided so that objects themselves might be seen divorced from the context of surrounding objects, on their own terms. It is difficult to imagine an interior space in which all of the objects command equal attention, but one example of this object autonomy and democratic arrangement of space is his box shapes, which he argued could only be boxes. The objects were not privileged above each other and were seen as part of the ‘empty’ space around them.

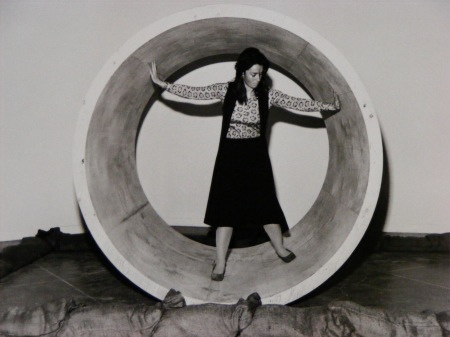

Also very important in the minimalist movement was writer, sculptor and conceptual artist Robert Morris (b.1931), particularly in his exploration of the position of bodies in space. Similarly to Judd, Morris was interested in the relationship between object, viewer and environment, but Morris put more energy into performing this relationship theatrically. He used visual narrative to describe events and ideas, whereas Judd was more concerned with the position of the static object.

With Morris's 1971 wheel piece (above) it is clear that the contours and aesthetic dimensions of the sculpture are very much imbedded in the same minimalist ethos as Judd’s. Yet unlike Judd, the spectator’s interaction with this piece extends to physical contact. The audience is encouraged to enter into the wheel: to know it in a bodily sense as well as visually.

The 1960s minimalist movement redefined spatial and object relations and questioned the position and existence of the boundary between ‘art’ and ‘everyday objects’. Strong trends in contemporary interior design – for example, the concept of ‘open plan living’ and the emphasis on sparse décor - are probably more influenced by minimalism than any other art movement.